Riemannian manifold

In Riemannian geometry and the differential geometry of surfaces, a Riemannian manifold or Riemannian space (M,g) is a real differentiable manifold M in which each tangent space is equipped with an inner product g, a Riemannian metric, which varies smoothly from point to point. The terms are named after German mathematician Bernhard Riemann.

A Riemannian metric makes it possible to define various geometric notions on a Riemannian manifold, such as angles, lengths of curves, areas (or volumes), curvature, gradients of functions and divergence of vector fields.

Contents |

Introduction

In 1828, Carl Friedrich Gauss proved his Theorema Egregium (remarkable theorem in Latin), establishing an important property of surfaces. Informally, the theorem says that the curvature of a surface can be determined entirely by measuring distances along paths on the surface. That is, curvature does not depend on how the surface might be embedded in 3-dimensional space. See differential geometry of surfaces. Bernhard Riemann extended Gauss's theory to higher dimensional spaces called manifolds in a way that also allows distances and angles to be measured and the notion of curvature to be defined, again in a way that was intrinsic to the manifold and not dependent upon its embedding in higher-dimensional spaces. Albert Einstein used the theory of Riemannian manifolds to develop his General Theory of Relativity. In particular, his equations for gravitation are restrictions on the curvature of space.

Overview

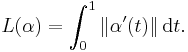

The tangent bundle of a smooth manifold M assigns to each fixed point of M a vector space called the tangent space, and each tangent space can be equipped with an inner product. If such a collection of inner products on the tangent bundle of a manifold varies smoothly as one traverses the manifold, then concepts that were defined only pointwise at each tangent space can be extended to yield analogous notions over finite regions of the manifold. For example, a smooth curve α(t): [0, 1] → M has tangent vector α′(t0) in the tangent space TM(α(t0)) at any point t0 ∈ (0, 1), and each such vector has length ‖α′(t0)‖, where ‖·‖ denotes the norm induced by the inner product on TM(α(t0)). The integral of these lengths gives the length of the curve α:

Smoothness of α(t) for t in [0, 1] guarantees that the integral L(α) exists and the length of this curve is defined.

In many instances, in order to pass from a linear-algebraic concept to a differential-geometric one, the smoothness requirement is very important.

Every smooth submanifold of Rn has an induced Riemannian metric g: the inner product on each tangent space is the restriction of the inner product on Rn. In fact, as follows from the Nash embedding theorem, all Riemannian manifolds can be realized this way. In particular one could define Riemannian manifold as a metric space which is isometric to a smooth submanifold of Rn with the induced intrinsic metric, where isometry here is meant in the sense of preserving the length of curves. This definition might theoretically not be flexible enough, but it is quite useful to build the first geometric intuitions in Riemannian geometry.

Riemannian manifolds as metric spaces

Usually a Riemannian manifold is defined as a smooth manifold with a smooth section of the positive-definite quadratic forms on the tangent bundle. Then one has to work to show that it can be turned to a metric space:

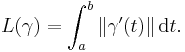

If γ: [a, b] → M is a continuously differentiable curve in the Riemannian manifold M, then we define its length L(γ) in analogy with the example above by

With this definition of length, every connected Riemannian manifold M becomes a metric space (and even a length metric space) in a natural fashion: the distance d(x, y) between the points x and y of M is defined as

- d(x,y) = inf{ L(γ) : γ is a continuously differentiable curve joining x and y}.

Even though Riemannian manifolds are usually "curved," there is still a notion of "straight line" on them: the geodesics. These are curves which locally join their points along shortest paths.

Assuming the manifold is compact, any two points x and y can be connected with a geodesic whose length is d(x,y). Without compactness, this need not be true. For example, in the punctured plane R2 \ {0}, the distance between the points (−1, 0) and (1, 0) is 2, but there is no geodesic realizing this distance.

Properties

In Riemannian manifolds, the notions of geodesic completeness, topological completeness and metric completeness are the same: that each implies the other is the content of the Hopf-Rinow theorem.

Riemannian metrics

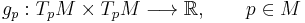

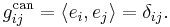

Let M be a differentiable manifold of dimension n. A Riemannian metric on M is a family of (positive definite) inner products

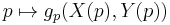

such that, for all differentiable vector fields X,Y on M,

defines a smooth function M → R.

More formally, a Riemannian metric  is a symmetric (0,2)-tensor that is positive definite (i.e. g(X,X) > 0 for all tangent vectors X ≠ 0).

is a symmetric (0,2)-tensor that is positive definite (i.e. g(X,X) > 0 for all tangent vectors X ≠ 0).

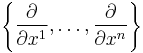

In a system of local coordinates on the manifold M given by n real-valued functions x1,x2, …, xn, the vector fields

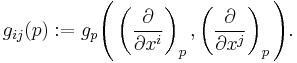

give a basis of tangent vectors at each point of M. Relative to this coordinate system, the components of the metric tensor are, at each point p,

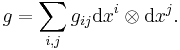

Equivalently, the metric tensor can be written in terms of the dual basis {dx1, …, dxn} of the cotangent bundle as

Endowed with this metric, the differentiable manifold (M,g) is a Riemannian manifold.

Examples

- With

identified with

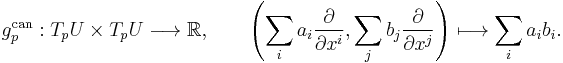

identified with  , the standard metric over an open subset

, the standard metric over an open subset  is defined by

is defined by

- Then g is a Riemannian metric, and

- Equipped with this metric, Rn is called Euclidean space of dimension n and gijcan is called the (canonical) Euclidean metric.

- Let (M,g) be a Riemannian manifold and

be a submanifold of M. Then the restriction of g to vectors tangent along N defines a Riemannian metric over N.

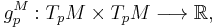

be a submanifold of M. Then the restriction of g to vectors tangent along N defines a Riemannian metric over N. - More generally, let f:Mn→Nn+k be an immersion. Then, if N has a Riemannian metric, f induces a Riemannian metric on M via pullback:

- This is then a metric; the positive definiteness follows of the injectivity of the differential of an immersion.

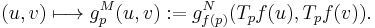

- Let (M,gM) be a Riemannian manifold, h:Mn+k→Nk be a differentiable map and q∈N be a regular value of h (the differential dh(p) is surjective for all p∈h-1(q)). Then h-1(q)⊂M is a submanifold of M of dimension n. Thus h-1(q) carries the Riemannian metric induced by inclusion.

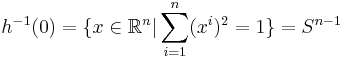

- In particular, consider the following map :

- Then, 0 is a regular value of h and

- is the unit sphere

. The metric induced from

. The metric induced from  on

on  is called the canonical metric of

is called the canonical metric of  .

.

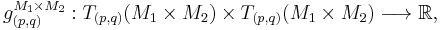

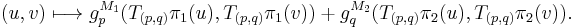

- Let

and

and  be two Riemannian manifolds and consider the cartesian product

be two Riemannian manifolds and consider the cartesian product  with the product structure. Furthermore, let

with the product structure. Furthermore, let  and

and  be the natural projections. For

be the natural projections. For  , a Riemannian metric on

, a Riemannian metric on  can be introduced as follows :

can be introduced as follows :

- The identification

- allows us to conclude that this defines a metric on the product space.

- The torus

possesses for example a Riemannian structure obtained by choosing the induced Riemannian metric from

possesses for example a Riemannian structure obtained by choosing the induced Riemannian metric from  on the circle

on the circle  and then taking the product metric. The torus

and then taking the product metric. The torus  endowed with this metric is called the flat torus.

endowed with this metric is called the flat torus.

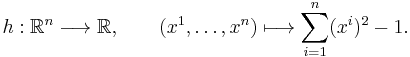

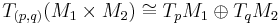

- Let

be two metrics on

be two metrics on  . Then,

. Then,

- is also a metric on M.

The pullback metric

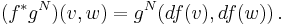

If f:M→N is a differentiable map and (N,gN) a Riemannian manifold, then the pullback of gN along f is a quadratic form on the tangent space of M. The pullback is the quadratic form f*gN on TM defined for v, w ∈ TpM by

where df(v) is the pushforward of v by f.

The quadratic form  is in general only a semi definite form because

is in general only a semi definite form because  can have a kernel. If f is a diffeomorphism, or more generally an immersion, then it defines a Riemannian metric on M, the pullback metric. In particular, every embedded smooth submanifold inherits a metric from being embedded in a Riemannian manifold, and every covering space inherits a metric from covering a Riemannian manifold.

can have a kernel. If f is a diffeomorphism, or more generally an immersion, then it defines a Riemannian metric on M, the pullback metric. In particular, every embedded smooth submanifold inherits a metric from being embedded in a Riemannian manifold, and every covering space inherits a metric from covering a Riemannian manifold.

Existence of a metric

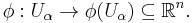

Every paracompact differentiable manifold admits a Riemannian metric. To prove this result, let M be a manifold and {(Uα, φ(Uα))|α∈I} a locally finite atlas of open subsets U of M and diffeomorphisms onto open subsets of Rn

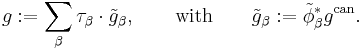

Let τα be a differentiable partition of unity subordinate to the given atlas. Then define the metric g on M by

where gcan is the Euclidean metric. This is readily seen to be a metric on M.

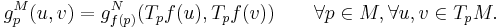

Isometries

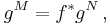

Let  and

and  be two Riemannian manifolds, and

be two Riemannian manifolds, and  be a diffeomorphism. Then, f is called an isometry, if

be a diffeomorphism. Then, f is called an isometry, if

or pointwise

Moreover, a differentiable mapping  is called a local isometry at

is called a local isometry at  if there is a neighbourhood

if there is a neighbourhood  ,

,  , such that

, such that  is a diffeomorphism satisfying the previous relation.

is a diffeomorphism satisfying the previous relation.

Riemannian manifolds as metric spaces

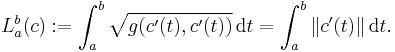

A connected Riemannian manifold carries the structure of a metric space whose distance function is the arclength of a minimizing geodesic.

Specifically, let (M,g) be a connected Riemannian manifold. Let ![c:[a,b]\rightarrow M](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/54fe4ca6c95b59f5e17ecfbe4549e6e7.png) be a parametrized curve in M, which is differentiable with velocity vector c′. The length of c is defined as

be a parametrized curve in M, which is differentiable with velocity vector c′. The length of c is defined as

By change of variables, the arclength is independent of the chosen parametrization. In particular, a curve ![[a,b]\rightarrow M](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/913850acdfd37932c568d2fd8dadfe99.png) can be parametrized by its arc length. A curve is parametrized by arclength if and only if

can be parametrized by its arc length. A curve is parametrized by arclength if and only if  for all

for all ![t\in[a,b]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c9ef8c742260828c469822e9c5dbe2c9.png) .

.

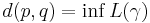

The distance function d : M×M → [0,∞) is defined by

where the infimum extends over all differentiable curves γ beginning at p∈M and ending at q∈M.

This function d satisfies the properties of a distance function for a metric space. The only property which is not completely straightforward is to show that d(p,q)=0 implies that p=q. For this property, one can use a normal coordinate system, which also allows one to show that the topology induced by d is the same as the original topology on M.

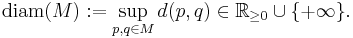

Diameter

The diameter of a Riemannian manifold M is defined by

The diameter is invariant under global isometries. Furthermore, the Heine-Borel property holds for (finite-dimensional) Riemannian manifolds: M is compact if and only if it is complete and has finite diameter.

Geodesic completeness

A Riemannian manifold M is geodesically complete if for all  , the exponential map

, the exponential map  is defined for all

is defined for all  , i.e. if any geodesic

, i.e. if any geodesic  starting from p is defined for all values of the parameter

starting from p is defined for all values of the parameter  . The Hopf-Rinow theorem asserts that M is geodesically complete if and only if it is complete as a metric space.

. The Hopf-Rinow theorem asserts that M is geodesically complete if and only if it is complete as a metric space.

If M is complete, then M is non-extendable in the sense that it is not isometric to an open proper submanifold of any other Riemannian manifold. The converse is not true, however: there exist non-extendable manifolds which are not complete.

See also

- Riemannian geometry

- Finsler manifold

- sub-Riemannian manifold

- pseudo-Riemannian manifold

- Metric tensor

- Hermitian manifold

- Space (mathematics)

References

- Jost, Jürgen (2008), Riemannian Geometry and Geometric Analysis (5th ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3540773405

- do Carmo, Manfredo (1992), Riemannian geometry, Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-0-8176-3490-2 [1]

External links

- L.A. Sidorov (2001), "Riemannian metric", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=R/r082180

![\tilde g:=\lambda g_0 %2B (1-\lambda)g_1,\qquad \lambda\in [0,1],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5e6700b68962fcdcec27a901d0719914.png)